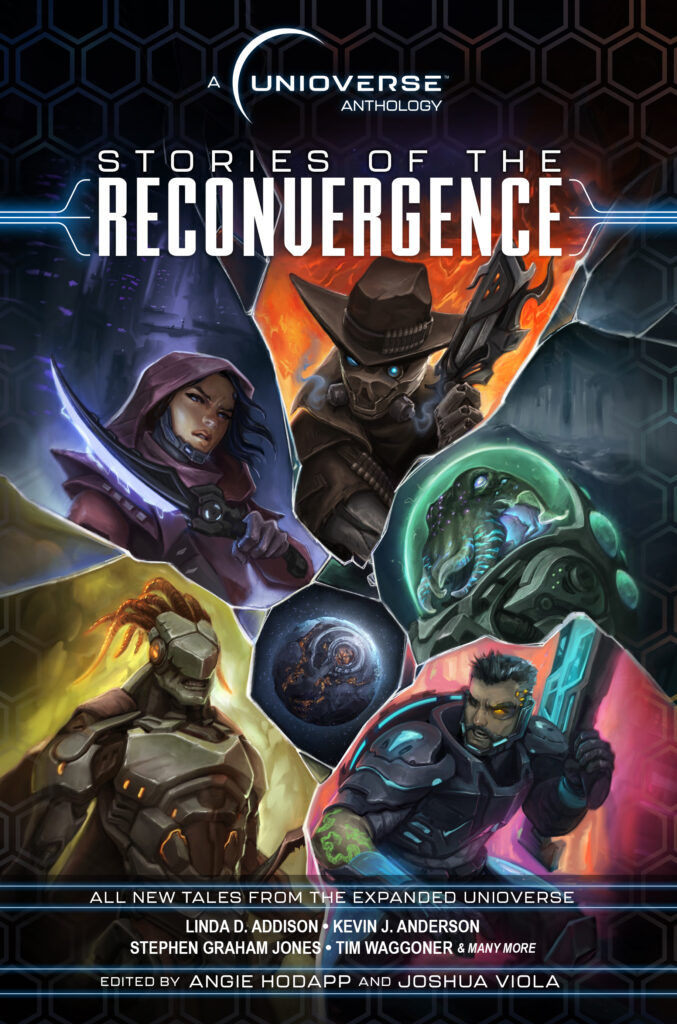

This post was authored by New York Times Bestselling author, Stephen Graham Jones (The Only Good Indians, My Heart is a Chainsaw). Graham Jones will also be contributing to Stories of the Reconvergence, the forthcoming Unioverse anthology of short fiction and poetry

You can tell a world—a Unioverse—is a productive storytelling space if, when you write within it, it’s just spinning off more and more story elements. Some science fiction writer from decades and decades ago, who I’m about to violently misparaphrase, said that what makes a place real for the reader isn’t the schematics and the history, the climate and the technology, the language and the look, it’s the third- or fifth-level repercussions of all that climate and language and history. Like, how in Ender’s Game, Ender’s name comes indirectly from protocols built into that culture, that era, but it’s not the first thing you guess when given those protocols. How in Altered Carbon, these re-sleeving capabilities have of course led to military units specializing in gaining control of their bodies quicker, to have a tactical advantage . . . but this also leads to methuselahs. Or, in our own world: introduce franchise horror characters, and, years later, you get Cthulhu plushies and Funko Pop Freddy Kruegers, which I’m pretty sure none of us could have ever guessed.

Drop a pebble into the pond of reality, and characters in stories will be surfing those distant, third- and fifth-level ripples for years and years.

By the time I dropped into the Unioverse, that pebble had already been dropped, and my characters were way out at the edge of the pond, riding the ripples. I’ve written for a few pre–existing properties before, and for each I usually get a bible, outlining what I can or can’t do. But, really, with work done within these pre–existing worlds, the cardinal rule is always “don’t break the place up.” This is why tie-in novels usually happen in a little narrative eddy off to the side, where A) nothing can get broken, and B) everything can reset after, such that the audience doesn’t need to engage this tie-in, but, if they do, it’s not going to mess anything up for them, either.

The Unioverse is a little different to work within, though. For a couple of reasons. The first is that, unlike nearly every other franchise and property, this one isn’t a snowball that’s been rolling for decades, picking up different, often contradictory “rules” along the way. Rather, the Unioverse has been completely thought-out all at once. In comic book terms, you could say that this is Ultimate Spider-Man, not decades of Amazing and Spectacular done by a host of writers, meant to somehow all be the same character, the same arc. In the Unioverse, there’s no retcon necessary to tell the next installment.

And? “Next” isn’t even the right word, there, which is the second reason the Unioverse is a bit different to work within. This isn’t about sequence or progression, and there’s no quest, no common goal. Rather, the Unioverse . . . it’s sort of like Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, I guess? It’s a place where all the stories happen, but across time, and without relation to each other. It’s an open world, where you make your own stories. And, instead of a phonebook of a bible, there’s a wiki you can refer to when making those stories.

Trick is, though, the Unioverse’s inbuilt “rules”—not the right word, quite—aren’t bumpers making your bowling ball find the pins eventually, but rather answers to questions your story or game or adventure is probably already asking, fundaments that push you forward rather than hold you back. They’re the backdrop, they’re the physics, but, if we’re sticking with the bowling thing, then the alley, man, it’s twenty lanes wide: there’s so much room to operate.

Check out Stephen Graham Jones talking about the Unioverse on our Worldbuilding Secrets podcast!

Example: in my story “The Distance,” of course the Creator tech is inviolable—if it’s not, then the physics of the Unioverse crumble. But, since that Creator tech’s been part of things for five hundred years, I had to imagine that, first, there would be all kinds of rumors and theories about its source, its inner workings, its permeability. Second, though—and this was the fun part—I had to suspect that, while people can’t imitate it, they probably can retrofigure back from it, to try to get to some version of the same place. As in, they can see, via Creator tech, that this or that is possible, and so, with that assurance, they delve in with their own limited tech, try to accomplish something . . . if not the same, then in the same vein, anyway. Or, as close as they can get. “Sys tech,” it’s called in my story: wholly inferior to Creator tech, but at least trying to approach that same level of competence.

And then, too, my protagonist being an animal smuggler—everyone’s got their specialty—that left me with the much sought-after obligation to dream up animal after animal, from planet after planet, even down to deep-space carrion mites.

The only thing I can imagine that might be half as much as fun as dreaming up alien pets would be racehorse naming. But? With these animals, I even get to do a little of that naming, so . . . best of all possible worlds, here, yes. Or, rather, best of all Unioverses, that being the one where I can have giant, world-changing fish-worms and bird-things that spout insults.

Hope y’all like the story, but, more than that, I hope you have fun jumping all through this place. You won’t understand the circuitry—it’s Creator tech, nobody gets it—but that doesn’t mean you can’t ride it to the end of known space, and then go back, ride it out a different direction as well.

Stephen Graham Jones